The King House Restoration

The King House, standing proud on a quiet Bristol street, has watched over two centuries of history unfold. It us the oldest house in Bristol. Built in 1814, it began as a modest 2-over-2 Georgian home with a central hall and two attic rooms reserved for the house slaves who labored there. Three presidents have slept here and the inception of the town happened within its walls. Its sturdy stone foundation and hand-hewn timbers were the work of early craftsmen who built to last, using local materials and skill that has kept the house standing through wars, economic booms and busts, and generations of change. Over time, the King House grew and evolved, reflecting the aspirations of each family who called it home. By the late 19th century, it had undergone multiple renovations, each adding layers of style and character without erasing the original bones.

The King Family Legacy

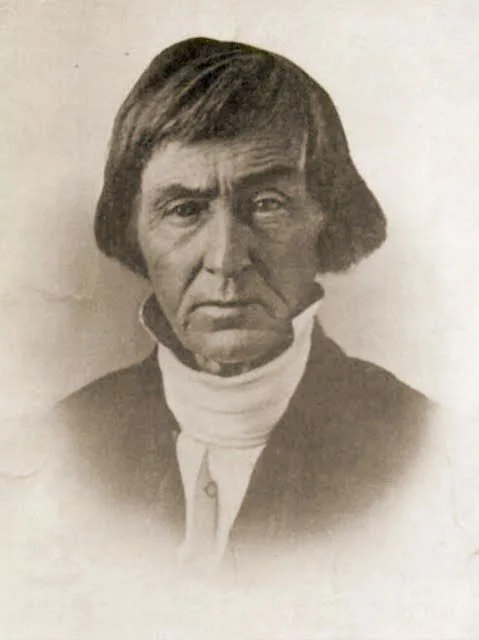

In the wild backcountry of what was then the far edge of Virginia, a man named Colonel James King set down roots. Born in 1752, he came of age when this land was still contested ground between settlers and native peoples. He married into the Goodson family, another clan of hardy pioneers, and began building something more permanent than log cabins and corn patches. His fortune lay in iron. Along Beaver Creek, where the waters rushed down from the knobs, he raised furnaces and forges. The smoke from his Beaver Creek Iron Works curled into the sky long before Bristol was even a notion. Travelers recalled seeing sparks dancing above the treetops at night, a sure sign that civilization—and industry—were taking hold in the wilderness.

Colonel King’s iron was bartered as money itself, carted by wagon to the Boat Yard at Kingsport, floated downriver to Natchez and even New Orleans. Folks said his bar iron was “of the best and most approved quality.” But Colonel King was more than an ironmaster. After the Revolution, he purchased the old Shelby fort site on Beaver Creek—the stockaded station where General Evan Shelby had once mustered men against both Cherokee and British. Where once stood palisades and rifle slits, the Colonel raised a plantation, with mills, cattle, and a brick house that looked down over what locals began to call King’s Meadows. When the Colonel died in 1825, his gravestone was no ordinary slab of stone. It was cast in iron—his own product—and bore a simple, enduring phrase: “A Patriot of 1776.”

Into this inheritance stepped his son, James King, Jr., born in 1791. Folks knew him not only as a planter but as the Reverend James King, a Presbyterian minister with a sober manner and a keen sense of stewardship. Where his father had built with iron and timber, James built with faith, community, and vision. He preached at early churches along the Holston, but he also dreamed of a greater institution. It was James King who gave the land for King College—what we now know as King University. That gift tied the family name forever to education and the gospel.

Life at King’s Meadows revolved around his great brick house on the hill. In 1839, James established the Sapling Grove Post Office right there in his own home. Travelers coming along the Abingdon-to-Blountville stage line would stop for the mail, rest their horses, and sometimes stay for a word of prayer with the Reverend.

For years, King’s Meadows was just that—fields of grass, dotted with cattle, crossed by wagon roads. But in the 1840s, word spread that two railroads might intersect there. James’s son-in-law, Joseph R. Anderson, saw the opportunity clear as day. With King’s blessing, Anderson laid out streets and lots upon the Reverend’s land. Thus was born the town of Bristol, carved from the heart of the King plantation. What had once been ironworks and meadows now sprouted storefronts and depots. The whistle of locomotives soon replaced the clang of triphammers.

Today, the Kings’ story lingers everywhere. At King University, a monument preserves pieces of the old ironworks machinery. The King–Lancaster–McCoy–Mitchell House still stands, a silent witness to the founding of a town. And somewhere under the grass and asphalt of Bristol lie the meadows where cattle grazed and a minister dreamed of what might be. The Kings were more than one family’s tale; they were the bridge between frontier and city, between wilderness and permanence. The father forged iron to hold the land; the son forged institutions and faith to hold a people. Together, they turned Beaver Creek’s smoke and meadows into the foundations of a community that still bears their imprint.

The story of the Mitchells in Bristol begins with J.D. and Louise Mitchell, who became stewards of one of the town’s most important historic homes in the late 19th and early 20th century. The house itself already carried a rich legacy, having been tied to the King family and the founding of Bristol. Under the Mitchells, it remained not just a residence but a landmark of continuity, a place where faith, family, and community life converged.

J.D. Mitchell was remembered as a man of steady character, involved in business and farming, respected for his honesty and leadership. His wife, Louise, balanced him with grace and hospitality, making their home a center of warmth and church-centered community gatherings. Together, they ensured that the house on the hill continued as a hub of stability through years when Bristol was transforming from a modest railroad town into a bustling city.

Their children, including Downman and Margaret Mitchell, carried the family name into the next generation. Downman followed in his father’s steps with quiet strength and local involvement, while Margaret was known for her spirited intelligence and devotion to the church and civic causes. Both reflected the values instilled by J.D. and Louise: a deep sense of responsibility to family, faith, and the broader Bristol community. As the decades passed, the Mitchell family’s presence became part of Bristol’s identity. They were not the city’s wealthiest or most flamboyant citizens, but they were pillars of constancy. Their care of the historic home tied the early frontier story of the Kings to the maturing city of Bristol. In many ways, the Mitchells acted as guardians of memory, bridging the old and the new.

Today, when the history of Bristol’s oldest homes is recalled, the Mitchell name stands alongside King, Lancaster, and McCoy, a reminder of how families sustained not only their households but the cultural heritage of an entire town. The Mitchells’ legacy is best remembered not in singular achievements, but in their enduring role as keepers of history and community life.

When my wife, Monica, and I became the stewards of the King House, we knew we weren’t just buying a home; we were inheriting a piece of living history. The property had its share of mysteries: Which portions were truly from 1814, and which had been altered later? Why were certain doors oddly placed, and why did some rooms feel like they belonged to different centuries? Sorting out those questions became a labor of love, involving months of research, long hours spent in dusty archives, and countless evenings poring over the original blueprints by lamplight. Slowly, the story of the house began to reveal itself—along with its needs.

The restoration has been a monumental undertaking. We’ve approached each decision with the same question: “What would the original craftsmen do?” Where possible, we have preserved original woodwork, patching rather than replacing. We’ve painstakingly repaired plaster walls rather than covering them with modern materials, ensuring that the imperfections—the little ripples and hand-tool marks—remain as part of the house’s charm. Every board, every nail, every hinge we’ve reused tells a story. Modern updates, where absolutely necessary for safety and comfort, have been done with care so they don’t jar against the home’s historic fabric.

One of the most significant transformations came in 1892, when H.E. McCoy purchased the property and undertook a major renovation. He altered the footprint, removing two of the original rooms and adding more elaborate architectural flourishes in keeping with the Victorian tastes of the era. Just a decade later, in 1902, another renovation followed, and the original blueprints from both these periods—miraculously preserved—would one day become a guiding light for us during our own restoration efforts. Those drawings documented every curve of the staircase, every molding profile, and even the precise spiral of the handrail, providing an intimate portrait of the house when it was not yet seventy years old. J.D Mitchell and his wife Louise were responsible for that remodel. They had two children- Downman and Margaret. Margaret lived in the house for 100 years. In her will, she left the property to King University, who maintained it for 17 years. In 2020, the college began a search for a new owner. The will stipulated that the university could not sell the property, but could transfer it to a qualified person who could restore it and maintain it. Wee applied and was selected. We paid $32 to have the title transfered into our name and the rest is history.

The Restoration

Restoring a home like this isn’t just about materials—it’s about spirit. Walking through the halls, I sometimes think about the families who lived here before us: the laughter that must have filled the parlor, the quiet grief that may have shadowed the rooms during hard times, the generations of footsteps worn into the floors. We see ourselves as caretakers, keeping the King House alive so that future generations can experience the same sense of connection we feel every day. Our work is not finished—it may never truly be “finished”—but each completed project brings the home a little closer to its former glory.

The King House Today

Today, the King House is once again a place of beauty and hospitality. Visitors are often struck by the way it seems to breathe, as if relieved to have its dignity restored. It’s a reminder that old houses don’t just endure—they adapt, they survive, and, with the right hands to guide them, they thrive. Our hope is that the King House will stand another two hundred years, bearing witness to the stories yet to come, just as it has for the past two centuries.